Blog

Why Prayer Isn’t just about the Pray-er

Here’s a repost from the Spring of 2013, but it goes with tonight’s study in the Sermon on the Mount. I’ll probably reference this tonight, so if you happen to be checking this blog before joining us, you get a heads up!

How can prayer be meaningful, when God knows everything that’s going to happen already? Why should we pray when God has his plan that “he’s going to work out anyway”? The answer is–God is a Trinity! If that answer doesn’t make sense to you, read on…

These are some amazing quotes from Andrew Murray on why prayer is possible at all–and it has to do with the nature of God. Check it out and get blessed…

…And so there was in the very Being and Life of God an asking of which prayer on earth was to be the reflection and the outflow. It was not without including this that Jesus said, “I knew that Thou always hearest me.” Just as the Sonship of Jesus on earth may not be separated from His Sonship in heaven, even so with His prayer on earth, it is the continuation and the couterpart of His asking in heaven. The prayer of the man Christ Jesus is the link between the eternal asking of the only-begotten Son in the bosom of the Father and the prayer of men upon earth.

Prayer has its rise and its deepest source in the very Being of God.

In the bosom of Deity nothing is ever done without prayer–the asking of the Son and the giving of the Father.

One of the secret difficulties with regard to prayer–one which, though not expressed, does often really hinder prayer–is derived from the perfection of God, in His absolute independence of all that is outside of Himself. Is He not the Infinite Being who owes what He is to Himself alone, who determines Himself, and whose wise and holy will has determined all that is to be? How can prayer influence Him, or He be moved by prayer to do what otherwise would not be done? Is not the promise of an answer to prayer simply a condescension to our weakness? Is what is said of the power…of prayer anything more than an accommodation to our mode of thought, because the Deity never can be dependent on any action from without for its doings? And is not the blessing of prayer simply the influence it exercises upon ourselves?

In seeking an answer to such questions, we find the key in the very being of God, in the mystery of the Holy Trinity.

If God was only one Person, shut up within Himself, there could be no thought of nearness to Him or influence on Him.

But in God there are three Persons. In God we have Father and Son, who have in the Holy Spirit their living bond of unity and fellowship. When eternal Love begat the Son, and the Father gave the Son as the Second Person a place next Himself as His Equal and His Counsellor, there was a way opened for prayer and its influence in the very inmost life of Deity itself. Just as on earth, so in heaven the whole relation between Father and Son is that of giving and taking.

These quotes are in Fred Sanders’ book The Deep Things of God. Sanders goes on to explain a little more what he sees in Murray’s thinking:

Crucial for Murray was to resist the urge to think of some will of God that is antecedent to the Son and the Father, or some decision that was made behind the back of the Trinity, in the oneness of God that is not already triune. There is no such God, so there is no such divine will. The divine will is Trinitarian and is worked out according to the asking-and-granting structure revealed in the Son: This may help us somewhat to understand how the prayer of man, coming through the Son, can have effect upon God.

The decrees of God are not decisions made by Him without reference to the Son, or His petition, or the petition to be sent up through Him. By no means.

The Lord Jesus is the first-begotten, the Head and Heir of all things: all things were created through Him and unto Him, and all things consist in Him. In the counsels of the Father, the Son, as Representative of all creation, had always a voice; in the decrees of the eternal purpose there was always room left for the liberty of the Son as Mediator and Intercessor, and so for the petitions of all who draw nigh to the Father in the Son.

Thoughts on the Decision

I have in front of me a printout of the full Obergefell v. Hodges decision handed down by the Supreme Court today. I plan on working through it in the next few days. If you’d like to join me, you can download it and print it out here.

Already, as we have come to expect, a few excellent responses to today’s events have been published. In case you haven’t seen them yet, here are a couple links.

Russell Moore, President of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, has a response in the Washington Post entitled “Why the church should neither cave nor panic about the decision on gay marriage.” He writes:

So how should the church respond? First of all, the church should not panic. The Supreme Court can do many things, but the Supreme Court cannot get Jesus back in that tomb. Jesus of Nazareth is still alive. He is still calling the universe toward his kingdom…

Let’s also recognize that if we’re right about marriage, and I believe we are, many people will be disappointed in getting what they want. Many of our neighbors believe that a redefined concept of marriage will simply expand the institution (and, let’s be honest, many will want it to keep on expanding). This will not do so, because sexual complementarity is not ancillary to marriage. The church must prepare for the refugees from the sexual revolution.

Definitely check out the whole article.

Joe Carter has a quick info piece just in case you’re not up to speed on the details of the decision. He also posted 50 Key Quotes from the Supreme Court’s Same-Sex Marriage Ruling, if you don’t want to comb through the whole thing yourself. In fact, the ERLC’s Archive page has a bunch of great articles like that one.

I’m sure we’ll all read more over the next few days. But I thought it would be good to end with one more quote from Moore’s Washington Post piece. When false things are elevated and lauded, let’s remember the most true things:

This gives the church an opportunity to do what Jesus called us to do with our marriages in the first place: to serve as a light in a dark place. Permanent, stable marriages with families with both a mother and a father may well make us seem freakish in 21st-century culture.

We should not fear that.

We believe stranger things than that.

We believe a previously dead man is alive, and will show up in the Eastern skies on a horse.

We believe that the gospel can forgive sinners like us and make us sons and daughters. Let’s embrace the sort of freakishness that saves.

The Glory of Plodding

Ever feel like your life is a repetitive drudgery? Ever feel like church is that? (I really hope not, so many good things are going on at Calvary Philly…) If so, Kevin DeYoung has some essential thoughts for you:

The Glory of Plodding

by Kevin DeYoung

It’s sexy among young people — my generation — to talk about ditching institutional religion and starting a revolution of real Christ-followers living in real community without the confines of church. Besides being unbiblical, such notions of churchless Christianity are unrealistic. It’s immaturity actually, like the newly engaged couple who think romance preserves the marriage, when the couple celebrating their golden anniversary know it’s the institution of marriage that preserves the romance. Without the God-given habit of corporate worship and the God-given mandate of corporate accountability, we will not prove faithful over the long haul.

What we need are fewer revolutionaries and a few more plodding visionaries. That’s my dream for the church — a multitude of faithful, risktaking plodders. The best churches are full of gospel-saturated people holding tenaciously to a vision of godly obedience and God’s glory, and pursuing that godliness and glory with relentless, often unnoticed, plodding consistency.

My generation in particular is prone to radicalism without followthrough. We have dreams of changing the world, and the world should take notice accordingly. But we’ve not proved faithful in much of anything yet. We haven’t held a steady job or raised godly kids or done our time in VBS or, in some cases, even moved off the parental dole. We want global change and expect a few more dollars to the ONE campaign or Habitat for Humanity chapter to just about wrap things up. What the church and the world needs, we imagine, is for us to be another Bono — Christian, but more spiritual than religious and more into social justice than the church. As great as it is that Bono is using his fame for some noble purpose, I just don’t believe that the happy future of the church, or the world for that matter, rests on our ability to raise up a million more Bonos (as at least one author suggests). With all due respect, what’s harder: to be an idolized rock star who travels around the world touting good causes and chiding governments for their lack of foreign aid, or to be a line worker at GM with four kids and a mortgage, who tithes to his church, sings in the choir every week, serves on the school board, and supports a Christian relief agency and a few missionaries from his disposable income?

Until we are content with being one of the million nameless, faceless church members and not the next globe-trotting rock star, we aren’t ready to be a part of the church. In the grand scheme of things, most of us are going to be more of an Ampliatus (Rom. 16:8) or Phlegon (v. 14) than an apostle Paul. And maybe that’s why so many Christians are getting tired of the church. We haven’t learned how to be part of the crowd. We haven’t learned to be ordinary. Our jobs are often mundane. Our devotional times often seem like a waste. Church services are often forgettable. That’s life. We drive to the same places, go through the same routines with the kids, buy the same groceries at the store, and share a bed with the same person every night. Church is often the same too — same doctrines, same basic order of worship, same preacher, same people. But in all the smallness and sameness, God works — like the smallest seed in the garden growing to unbelievable heights, like beloved Tychicus, that faithful minister, delivering the mail and apostolic greetings (Eph. 6:21). Life is usually pretty ordinary, just like following Jesus most days. Daily discipleship is not a new revolution each morning or an agent of global transformation every evening; it’s a long obedience in the same direction.

It’s possible the church needs to change. Certainly in some areas it does. But it’s also possible we’ve changed — and not for the better. It’s possible we no longer find joy in so great a salvation. It’s possible that our boredom has less to do with the church, its doctrines, or its poor leadership and more to do with our unwillingness to tolerate imperfection in others and our own coldness to the same old message about Christ’s death and resurrection. It’s possible we talk a lot about authentic community but we aren’t willing to live in it.

The church is not an incidental part of God’s plan. Jesus didn’t invite people to join an anti-religion, anti-doctrine, anti-institutional bandwagon of love, harmony, and re-integration. He showed people how to live, to be sure. But He also called them to repent, called them to faith, called them out of the world, and called them into the church. The Lord “didn’t add them to the church without saving them, and he didn’t save them without adding them to the church” (John Stott).

“Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Cor. 13:7). If we truly love the church, we will bear with her in her failings, endure her struggles, believe her to be the beloved bride of Christ, and hope for her final glorification. The church is the hope of the world — not because she gets it all right, but because she is a body with Christ for her Head.

Don’t give up on the church. The New Testament knows nothing of churchless Christianity. The invisible church is for invisible Christians. The visible church is for you and me. Put away the Che Guevara t-shirts, stop the revolution, and join the rest of the plodders. Fifty years from now you’ll be glad you did.

You never know who you’re talking to.

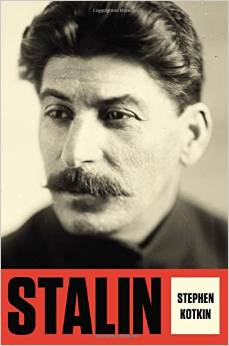

For Christmas my wife bought me Stephen Kotkin’s new biography of Ioseb Jughashvili, otherwise known to history as Joseph Stalin. It’s huge, so I’m nowhere near finished with it, but it has been an excellent read so far, full of tons of background history and information on everything from pre-WWI Europe to the reasons for (and nature of ) the Russian revolution. I guess you have to like history, but really, it’s great. Anyway, like all good books on history, it’s got lessons for our current times, and even more than that, it has food for thought for the Christian. For instance, in this passage, Kotkin discusses how unlikely it seems for someone from the edges of society to ascend to the top and into the center of a nation, from being a seemingly unimportant individual (a “no name”) to the most powerful person in a nation, or even in an era. And yet, it does happen. Kotkin writes:

For Christmas my wife bought me Stephen Kotkin’s new biography of Ioseb Jughashvili, otherwise known to history as Joseph Stalin. It’s huge, so I’m nowhere near finished with it, but it has been an excellent read so far, full of tons of background history and information on everything from pre-WWI Europe to the reasons for (and nature of ) the Russian revolution. I guess you have to like history, but really, it’s great. Anyway, like all good books on history, it’s got lessons for our current times, and even more than that, it has food for thought for the Christian. For instance, in this passage, Kotkin discusses how unlikely it seems for someone from the edges of society to ascend to the top and into the center of a nation, from being a seemingly unimportant individual (a “no name”) to the most powerful person in a nation, or even in an era. And yet, it does happen. Kotkin writes:

Stalin’s ascension to the top from an imperial periphery was uncommon but not unique.

Napoleone di Buonaparte had been born the second of eight children in 1769 on Corsica, a Mediterranean island annexed only the year before by France; that annexation (from the Republic of Genoa) allowed this young man of modest privilege to attend French military schools. Napoleon (in the French spelling) never lost his Corsican accent, yet he rose to become not only French general but, by age thirty-five, hereditary emperor of France.

Then plebeian Adolf Hitler was born entirely outside the country he would dominate: he hailed from the Habsburg borderlands, which had been left out of the 1871 German unification. In 1913 at age twenty-four, he relocated from Austria-Hungary to Munich, just in time; it turned out, to enlist in the imperial German army for the Great War. In 1923, Hitler was convicted of high treason for what came to be known as the Munich Beer Hall Putsch, but a German nationalist judge, ignoring the applicable law, refrained from deporting the non-German citizen. Two years later, Hitler surrendered his Austrian citizenship and became stateless. Only in 1932 did he acquire German citizenship, when he was naturalized on a pretext (nominally, appointed as a “land surveyor” in Braunschweig, a Nazi party electoral stronghold). The next year Hitler was named chancellor of Germany, on his way to becoming dictator.

By the standards of a Hitler or a Napoleon, Stalin grew up as an unambiguous subject of his empire, Russia, which had annexed most of Georgia fully seventy-seven years before his birth. Still, his leap from the lowly periphery was impossible.

Consider further that the young Jughashvili [Stalin’s last name by birth] could have died from smallpox, as did so many of his neighbors, or been carried off by the other fatal diseases that were endemic in the slums of Batum and Baku, where he agitated for socialist revolution. Competent police work could have had him sentenced to forced labor in a silver mine, where many a revolutionary met an early death. Jughashvili could have been hanged by the authorities in 1906-7 as part of the extrajudicial executions in the crackdown following the 1905 revolution (more than 1,100 were hanged in 1905-6)…

If Stalin had died in childhood or youth, that would not have stopped a world war, revolution, chaos, and likely some of authoritarianism redux in post-Romanov Russia. And yet the determination of this young man of humble origins to make something of himself, his cunning, his honing of organizational talents would help transform the entire structural landscape of the early Bolshevik revolution from 1917. Stalin brutally, artfully, indefatigably built a personal dictatorship within the Bolshevik dictatorship. Then he launched a saw through a bloody socialist remarking of the entire former empire, presided over a victory in the greatest war in human history, and took the Soviet Union to the epicenter of global affairs. More than for any other historical figure, even Gandhi or Churchill, a biography of Stalin, as we shall see, eventually comes to approximate a history of the world.

As I read this, it seemed to be a powerful illustration of that old cliché, “You never know who you’re talking to.” These very powerful (and powerfully terrible) men had moved through their youth as “normal” non-descript personalities. What if, at some early point in their life, someone had shared the gospel with them, and they had embraced it? It’s a good reminder–everyone we meet is important, and worth sharing with. First because they’re made in God’s image and God has sent his Son for them. And second, as this passage shows, because they will inevitably influence other lives, for good or evil. Even if it’s only friends and immediate family–how much impact does one mom or dad have on their kids? You start to realize how huge it is to influence someone for Christ. So many lives will be affected by each individual.

But how much more when we could be talking to someone who seems pretty normal, but who may one day end up in a position of power we couldn’t even imagine? History tells us this happens. When we take time to really lay out the gospel for that friend or stranger, could we be talking to someone who’s history may shape the history of the world? It’s possible!

A Woman You Should Know

Her book is at the top of the list of books I recently posted–the books which most influenced my early twenties. Elisabeth Elliot died yesterday. I heard the news and thought of all the time I have spend reading her writing, and how much her portrait of her first husband Jim, and her own thoughts, have helped and edified me. This eulogy by John Piper is completely fitting. Please take a few minutes to read it. And then go read her books!

Peaches in Paradise: Why I loved Elisabeth Elliot

by John Piper.

At 6:15 this morning, Elisabeth Elliot died. It is a blunt sentence for a blunt woman. This is near the top of why I felt such an affection and admiration for her.

Blunt — not ungracious, not impetuous, not snappy or gruff. But direct, unsentimental, no-nonsense, tell-it-like-it-is, no whining allowed. Just pull your britches on and go die for Jesus — like Mary Slessor and Gladys Aylward and Amy Carmichael and Gertrude Ras Egede and Eleanor Macomber and Lottie Moon and Roslind Goforth and Malla Moe, to name a few whom she admired.

Her first husband, Jim Elliot, was one of the five missionaries speared to death by the Huaorani Indians in Ecuador in 1956. Elisabeth immortalized that moment in mission history with three books, Through Gates of Splendor, Shadow of the Almighty, and The Savage My Kinsman, and established her voice for the cause of Christian missions and Christian womanhood and Christian purity in more than 20 other books, and 40 years of hard-hitting conference speaking.

Her Suffering

She was not just gutsy with her words. Their daughter was ten months old when Jim was killed. Elisabeth stayed on, working at first with the Quichua, but then, astonishingly, for two more years with the very tribe that had speared her husband.

In July 1997, I wrote this in my journal:

This morning, as I jogged and listened to a message by Elisabeth Elliot which she had given in Kansas City, I was deeply moved concerning my own inability to suffer magnanimously and without pouting. She was vintage Elliot and the message was the same as ever: Don’t get in touch with your feelings, submit radically to God, and do what is right no matter what. Put your love life on the altar and keep it there until God takes it off. Suffering is normal. Have you no scars, no wounds, with Jesus on the Calvary road?

Just like Jesus, and Jim Elliot, she called young people to come and die. Sacrifice and suffering were woven through her writing and speaking like a scarlet thread. She was not a romantic about missions. She disliked very much the sentimentalizing of discipleship.

We all know that missionaries don’t go, they “go forth,” they don’t walk, they “tread the burning sands,” they don’t die, they “lay down their lives.” But the work gets done even if it is sentimentalized! (The Gatekeeper)

The thread of suffering was not just woven through her words, but through her relationships. Not only did she lose her first husband to a violent death three years after they were married; she also lost her second husband Addison Leitch four years after her remarriage.

Now it’s time to reveal a little secret. For seventeen years, I have from time to time spoken of a certain woman on a panel with me about the topic of world missions. This woman had heard me speak on Christian Hedonism. So on the panel she said, “I don’t think you should say, ‘Pursue joy with all your might.’ I think you should say, ‘Pursue obedience with all your might.’” To this I responded, “But that’s like saying, ‘Don’t pursue peaches with all your might, pursue fruit.’”

Well, that was Elisabeth Elliot and the panel was at Caister (the EFIC summer gathering) on the east coast of England. She was allergic to anything that smacked of mushy, mawkish, sentimentalistic emotionalism. Amen, Elisabeth! O how I loved sparring with someone I could not have felt more in tune with.

Her Womanhood

And then there was her tough take on feminism and her magnificent vision of sexual complementarity. When Wayne Grudem and I looked around thirty years ago for articulate, strong, female complementarian voices to include in our book Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, she was at the top of the list. But the list was not long.

Partly because of her voice, that list today would be so long we would not know where to stop. I love her for this influence. Her chapter in our book is called “The Essence of Femininity: A Personal Perspective.” The title is intentionally (and typically) provocative. She was already seeing with the eyes of a prophetess.

Christian higher education, trotting happily along in the train of feminist crusaders, is willing and eager to treat the subject of feminism, but gags on the word femininity. Maybe it regards the subject as trivial or unworthy of academic inquiry. Maybe the real reason is that its basic premise is feminism. Therefore it simply cannot cope with femininity. (395–396)

She spoke, on the one hand, “from the vantage point of the ‘peasants’ in the Stone-Age culture where I once lived” (395), and on the other hand from a sophisticated vision of how the universe is put together:

What I have to say is not validated by my having a graduate degree or a positon on the faculty or administration of an institution of higher learning. . . . Instead, it is what I see as the arrangement of the universe and the full harmony and tone of Scripture. This arrangement is a glorious hierarchical order of graduated splendor, beginning with the Trinity descending through seraphim, cherubim, archangels, angels, men, and all lesser creatures, a mighty universal dance, choreographed for the perfection and fulfillment of each participant. (394)

When we deal with masculinity and femininity we are dealing with the “live and awful shadows of realities utterly beyond our control and largely beyond our direct knowledge,” as Lewis puts it. (397)

A Christian woman’s true freedom [and, of course, she would also say a Christian man’s true freedom] lies on the other side of a very small gate — humble obedience — but that gate leads out into a largeness of life undreamed of by the liberators of the world, to a place where the God-given differentiation between the sexes is not obfuscated but celebrated, where our inequalities are seen as essential to the image of God, for it is in male and female, in male as male and female as female, not as two identical and interchangeable halves, that the image is manifested. (399)

Her Teeth

Finally, I loved her because she never got her teeth fixed. I would still love her if she had gotten a dental makeover to pull her two front teeth together. But she didn’t. Am I ending on a silly note? You judge.

She was captured by Christ. She was not her own. She was supremely mastered, not by any ordinary man, but by the King of the universe. He had told her,

Do not let your adorning be external — the braiding of hair and the putting on of gold jewelry, or the clothing you wear — but let your adorning be the hidden person of the heart with the imperishable beauty of a gentle and quiet spirit, which in God’s sight is very precious . . . and do not fear anything that is frightening. (1 Peter 3:3–6)

Whether it was the spears of the Ecuadorian jungle or the standards of American glamor, she would not be cowed. “Do not fear anything that is frightening.” That is the mark of a daughter of Abraham. And in our culture one of the most frightening things women face is not having the right figure, the right hair, the right clothes — or the right teeth. Elisabeth Elliot was free from that bondage.

Finally, she wrote, “We are women, and my plea is Let me be a woman, holy through and through, asking for nothing but what God wants to give me, receiving with both hands and with all my heart whatever that is” (398).

That prayer was answered spectacularly this morning at 6:15. For her, from now on all fruit is peaches. I am eager to join her.

Three considerations when choosing a career.

We continue with wisdom for picking a career from Tim Keller’s book Every Good Endeavor.

What wisdom, then, would the Bible give us in choosing our work?…

First, if we have the luxury of options, we would want to choose work that we can do well. It should fit our gifts and our capacities. To take up work that we can do well is like cultivating our selves as gardens filled with hidden potential; it is to make the greatest room for the ministry of competence.

Second, because the main purpose of work that benefits others. We have to ask whether our work or organization or industry makes people better or appeals to the worst aspects of their characters. The answer will not always be black and white; in fact, the answer could differ from person to person. In a volume on the Christian approach to vocation, John Bernbaum and Simon Steer presented the case of Debbie, a woman who made a great deal of money working for an interior-decorating company in Aspen, Colorado. The craft of interior design, like architecture or the arts, is a positive way to promote human well-being. But she often found herself using resources in ways that she could not reconcile with pursuing the common good. She left her career to work for a church and later for a U.S. senator. Debbie said, “Not that there was anything dishonest or illegal involved, but I was being paid on a commission basis – thirty percent of the gross profit. One client spent twenty thousand dollars [in the early 1980s] on furnishings for a ten-by-twelve [foot] room. I began to question my motivation for encouraging people to… spend huge sums of money in furniture. So…I decided to leave.” This example is not about the value of interior design profession or the commission form of compensation. Rather, it illustrates the need for everyone to work out in clear personal terms how their work serves the world…

Third if possible, we do not simply wish to benefit our family, benefit the human community, and benefit ourselves – we also want to benefit our field of work itself. In Genesis 1 and 2, we saw that God not only cultivated his creation, but he created more cultivators. Likewise, our goal should not simply be to do work, but to increase the human race’s capacity to cultivate the created world. It is a worthy goal to want to make a contribution to your discipline, if possible; to show a better, deeper, fairer, more skillful, more ennobling way of doing what you do. Dorothy Sayers explores this point in her famous essay “Why Work?” She acknowledges that we should work for “the common good” and “for others” (as we observed in chapter 4), but she doesn’t want us to stop there. She says that the worker must “serve the work”:

The popular catchphrase of today is that it is everybody’s duty to serve the community, but … there is, in fact, a paradox about working to serve the community and it is this: that to aim directly at serving the community is to falsify the work … There are … very good reasons for this:

The moment you [only] think of serving other people, you begin to have a notation that other people owe you something for your pains; you begin to think that you have a claim on the community. You will begin to bargain for reward, to angle for applause, and to harbor a grievance if you are not appreciated. But if your mind is set upon serving the works, then you know you have nothing to look for; the only reward the work can give you is the satisfaction of beholding its perfection. The work takes all and gives nothing but itself; and to serve the work is a labor of pure love.

The only true way of serving the community is to be truly in sympathy with the community, to be oneself part of the community and then to serve the work… It is the work that serves the community; the business of the worker is to serve the work.

Sayer’s point is well taken and not often made or understood. It is possible to imagine you are “serving the community” because what you do is popular – at least for a time. However, you may no longer be serving the community – you may be using it for the way its approval makes you feel. But if you do your work so well that by God’s grace it helps others who can never thank you, or it helps those who come after you to do it better, then you know you are “serving the work,” and truly loving your neighbor.

Thoughts on Picking a Career

One of the unique things about the time and place we inhabit is that we are given choice for so many things. Young adults have the particularly odd privilege of being able to choose their career. Think about it—in how many places, for how much of history, has a young person been able to simply choose, from a seemingly unending list, what they want to pursue as their life’s work? The answer is, that’s pretty rare.

And yet, as many of us know first hand, the experience can be pretty overwhelming. It’s like walking up to a dinner buffet a mile long. Where do you even begin?

With this post and the next I’ll post sections from Tim Keller’s book Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work. In this passage he provides some practical counsel and helpful perspective about what to think through when you’re choosing a career.

Ecclesiastes says, “A person can do nothing better than to…find satisfaction in their own toil”. One of the reasons so many people find work to be unsatisfying is, ironically, that people today have more power to choose their line of work than did people in the past. Recently David Brooks wrote in the New York Times about an online discussion conducted by a Stanford professor with students and recent graduates about why so many students from the most exclusive universities go into either finance or consulting. Some defended their pathways; others complained that “the smartest people should be fighting poverty, ending disease and serving others, not themselves.” Brooks said that while the discussion was illuminating, he was struck by the unspoken assumptions:

Many of these students seem to have a blinker view of their options. There’s crass but affluent investment banking. There’s the poor but noble nonprofit world. And then there is the world of high-tech start-ups, which magically provides money and coolness simultaneously. But there was little interest in or awareness of the ministry, the military, the academy, government service or the zillion other sectors. Furthermore, few students showed any interest in working for a company that actually makes products…

Community service has become a patch for morality. Many people today have not been given vocabularies to talk about what virtue is, what character consists of, and in which way excellence lies, so they just talk about community service… In whatever field you go into, you will face greed, frustration and failure. You may find your life challenged by depression, alcoholism, infidelity, your own stupidity and self-indulgence… Furthermore … around what ultimate purpose should your life revolve? Are you capable of heroic self-sacrifice or is life just a series of achievement hoops? … You can devote your life to community service and be a total schmuck. You can spend your life on Wall Street and be a hero. Understanding heroism and schmuckdom requires fewer Excel spreadsheets, more Dostoyevsky and the Book of Job.

Brook’s first point is that so many college students do not choose work that actually fits within their limited imagination of how they can boost their own self-image. There were only three high-status kinds of jobs – those that paid well, those that directly worked on society’s needs, and those that had the cool factor. Because there is no longer an operative consensus on the dignity of all work, still less on the idea that in all work we are the hands and fingers of God serving the human community, in their minds they had an extremely limited range of career choices. That means lots of young adults are choosing work that doesn’t fit them, or fields that are too highly competitive for most people to do well in. And this sets many people up for a sense of dissatisfaction or meaninglessness in their work.

Perhaps it is related to the mobility of our urban culture and the resulting disruption of community, but in New York City many young people see the process of career selection more as the choice of an identity marker than a consideration of gifting and passions to contribute to the world. One young man explained, “I chose management consulting because it is filled with sharp people – the kind of people I want to be around.” Another said “I realize that if I stayed in education, I’d be embarrassed when I got to my five year college reunion, so I’m going to law school now.” Where one’s identity in prior generations might come from being the son of so-and-so or living in a particular part of town or being a member of a church or club, today young people are seeking to define themselves by the status of their work.

What wisdom, then, would the Bible give us in choosing our work?…

We’ll continue with Keller’s thoughts in the next post.

Prayer, Life, and a Video.

I recommend taking six minutes to check out this video and to think about our personal prayer lives, our experience of Christian community, our generosity, and joining the church for prayer next Sunday evening at 6 PM…

How not to be judgmental. (Notes from last night.)

Last night we continued our study of the Sermon on the Mount, looking at Matthew 7:1-5 and Jesus’ teaching on judging others. Here are the notes:

Matthew 7:1-6 // 6.8.15 // All about judging

7:1-2

Here Jesus teaches his followers to think about their own judgment first, and to keep it on their minds whenever they make judgment calls about other people. See also James 2:8-13.

To those who aren’t Jesus’ followers yet, these verses continue the message of 4:17 (“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!”) by instructing the world to repent in this way: The kingdom of heaven is coming–in response, stop ignoring the fact that all human activity will face the scrutiny of the final judgment, where everything about each person will be evaluated by none other than God himself.

7:3-4

Jesus clarifies the issue here by giving us more information. When he says, “judge not,” he’s talking about avoiding the kind of mentality that notices small flaws in others, while ignoring big flaws in ourselves. He’s teaching his followers not to try to address issues in other peoples’ lives when their own lives still needs addressing, especially if the basic issue is the same for both people.

To those who aren’t Jesus’ followers yet, these verses continue the message of 4:17 like this: The kingdom of heaven is coming–in response, stop passing judgment on others when the same issues are in your lives, or would be, if you had the opportunity and didn’t have to worry about consequences. Stop moralizing to everyone while you have the same issues raging in your lives. These things aren’t just for those who identify themselves as followers of Christ, they are a call to our culture–to all those who do not follow Christ, and yet who do have this issue of “judgmentalism” in their lives.

7:5

This verse is interesting, because here we see that Jesus doesn’t think it’s wrong to notice things that are wrong with other’s lives, if our own lives are clean, and we want to help. So he says, if you see things wrong with other people and with the world, the first thing to do is to have a life that is free from evil and harmful things, especially the evil you want to fix. Having sin in our own lives messes up our vision, and then we can’t help anything. If we get rid of those things from our lives (if we repent) we’ll have clear vision and we’ll actually be able to help people. (By the way, if you think about it, if someone actually has a speck in their eye, it’s incredibly painful, and it would be a loving thing to help someone get it out if they needed it.)

Putting it all together:

1. “Not judging” does not mean “not telling people they’re wrong.”

It’s not wrong to identify something that’s wrong in someone’s life (the “speck in the eye”). Our culture says this is what Jesus means by “judge.” But Jesus can’t mean simply, “never tell anyone they’re wrong,” or he wouldn’t have said what we have recorded in verse five.

And there’s a lot more along those lines. For instance, notice how contradictory it would be for Jesus to teach that no one should ever confront someone for sin in other’s lives, and then to say (and have his followers say) these things:

- Matthew 4:17 (By calling humanity to “repent” Jesus assumes there are things wrong with people’s lives, and that they need to change.)

- Matthew 18:15-17 (Jesus taught that his followers could notice sin in each other’s lives, and confront each other about it in the right way.)

- Mark 7:21-23, 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 (Jesus taught that certain things in human hearts were evil, and defiled people. His early messengers continued his teaching.)

- 1 Corinthians 5:9-13, 2 Thessalonians 3:6-15 (Jesus authoritative messengers applied his teachings by instructing Christians how to notice and deal with wrong things in each other’s lives.)

- Matthew 28:18-20 (Jesus’ main instruction to his followers about what to do after he ascended involved teaching them to obey his commands–and this would necessarily involve telling people to do some things and to stop doing other things.)

Maybe the key is found in this passage: John 8:2-11. We need to learn to speak like Jesus: “I don’t condemn you, go and sin no more.”

2. We are called to be people who don’t judge, but do help get rid of sin.

So, what Jesus teaches is not that his followers will never tell someone they’re wrong, but that his followers will not have nit-picking, critical spirits and lives full of the same sins they confront. They will have humility even as they courageously attempt to call those around them to repentance. They’ll be kind and large-hearted, and they’ll be sensitive and skilled at helping people, and willing to do the hard work it requires. See Galatians 6:1 and James 5:19.

3. We don’t have to make judgment calls unless God’s judgment requires it.

Whenever they can, followers of Jesus will avoid making judgments, and they’ll enjoy the freedom that brings to love people and serve God while they mind their own business. See Romans 14:1-4, 1 Corinthians 4:3-5, James 4:11-12, and especially Luke 12:32-38.

Two final Challenges:

- This part of Jesus’ teaching relieves us of the burden of making judgment calls, or having opinions, when God’s word hasn’t spoke or when it is unclear what should be said. We don’t need to speak, or have opinions, all the time.

- When I am criticizing someone, am I right at all? If I am thinking or speaking about a flaw they have, is it with a view to my own judgment? Am I addressing something forgetting that I will be judged by God, or because I will be judged by God.

What generosity costs…

This piece by Tim Challies goes exactly with our study from Monday night…

I was actually just starting to feel a little sorry for myself. I was on the sidelines at my daughter’s soccer game while a group of parents stood behind me laughing and chatting. As the game went on they talked and talked about all the great things they’ve done, the homes they’ve bought, the vacations they’ve enjoyed, the lessons their kids have taken. One even talked about his bright yellow Corvette that was parked conspicuously nearby.

Their lives sounded pretty good. They sounded better than mine, if I was comparing. I thought about what it must cost to take that annual trip to the Caribbean. I thought about what it must cost to get that new kitchen. I thought about the difference between a second car that is a sensible, family-friendly sedan and a second car that is built purely for thrills. And for a moment I wanted it. I wanted it all.

But my pathetic little pity party lasted only a moment before it struck me: The cost of all of that stuff is the cost of generosity. At least, it is for most of the people I know. Those donations to the church, those checks to the missionaries, those gifts to the ministries, those bills slipped discreetly to the person in need—tally them up and they could equal some extra vacations. Put them together and you could probably upgrade your kitchen this year instead of five years from now, or you could go up a model or two on the second vehicle. The Christians I know choose to downgrade their lifestyle in order to upgrade their giving.

And this, I think, is the enduring power and comfort of what Randy Alcorn calls the treasure principle: You can’t take it with you—but you can send it on ahead. The money isn’t gone. The money isn’t misused. It’s simply been redirected into a different kind of investment. “If we give instead of keep, if we invest in the eternal instead of in the temporal, we store up treasures in heaven that will never stop paying dividends. Whatever we store up on earth will be left behind when we leave. Whatever treasures we store up in heaven will be waiting for us when we arrive.” We find when we commit to this kind of generosity that there is greater joy both now and then.

You can’t keep up with the Joneses when you’re committed to radical generosity, and I think that’s exactly how God intends it.

Get In Touch

Got Questions or anything else? It’d be great to hear from you!

Feel free to contact us and get in touch.

Hope to hear from you soon!